Poet Gerard Hopkins Dies in Dublin from Typhoid Fever in 1889

Patrick Lonergan, The Hopkins Society,

Librarian,

KIldare Co. Council,

Newbridge, Co. Kildare

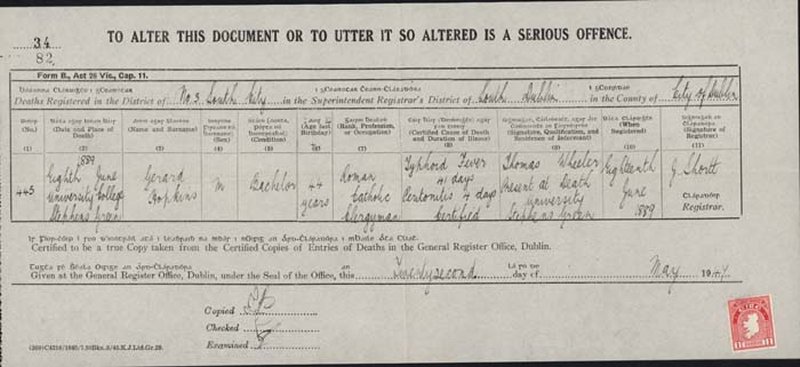

Gerard Manley Hopkins died on Saturday 08 June 1889, the vigil of Whit Sunday, at 85 St. Stephen's Green Dublin, then part of University College, following an illness of about six weeks' duration.

The certified cause of Hopkins' death was typhoid fever

, complicated by peritonitis.

Father Hopkins, teaching elementary Greek

whilst his mind climbed the clouds, also died here.

O faith in all he lost

John Berryman: Dream Song 377

Gerard Manley Hopkins died on Saturday 08 June 1889, the vigil of Whit Sunday, at No. 85 St. Stephen's Green Dublin, then part of University College, following an illness of about six weeks' duration. The certified cause of death was typhoid fever, complicated by peritonitis. He was buried on the following Tuesday, 11 June, in the Jesuit plot in Glasnevin cemetery

, on the north side of Dublin.

These are the bare facts. Today I want to look a little beyond those facts, at the events leading up

to and surrounding what Norman White

in his biography described as the sudden and meaningless

end to Hopkins's life.

This is an apt description of the death of a young man of 44, leaving both his parents alive, from an illness which, arguably, he should not have suffered. I will begin with some remarks on Hopkins' general health. He was a frail man, never robust, and prone to illness. He frequently suffered from physical and mental fatigue; there were, in his life, a number of recorded bouts of melancholy and depression; he regarded Monasterevin as a retreat in which he renewed his spirits during his never totally happy years in Dublin. His letters frequently complained of his poor health and after his death one of his contemporaries noted that he "looked older than his age". From the various references to his poor health, we get a picture of one who would not have offered much resistance to illness, which might go some way to explaining why he succumbed to an illness which affected no one else in his immediate vicinity.

I begin my account of Hopkins' final days on the significant date of 22 April 1889. On that day, he completed what was to be his final poem, To R.B. "R.B." was, of course, his friend Robert Bridges. A week later he sent the poem to Bridges, accompanied by a long letter in which he made a brief passing reference to being unwell:

I am ill today, but no matter for that as my spirits are good".

This was the first reference to what would be his final illness. In this letter, incidentally, he wrote of Miss Cassidy

, whom he described as an elderly lady who by often asking me down to Monasterevan and by the change and holiday her kind hospitality provides is become one of the props and struts of my existence

Four days later, on 03 May, his mother, Kate, received from him a brief letter in which he wrote that he was going early to bed as he was in some rheumatic fever. He felt that his illness was interfering with his work; he described it as occurring very inconveniently when I shd. be and am setting my Papers for the examination. Nor did he seem to regard it as very serious; he wrote I hope to be better tomorrow. If I am worse I may see the doctor. He did see the doctor. On the day when Kate received this letter, he was writing to his father Manley. He told him : I saw a doctor yesterday, who treated my complaint as a fleabite, a treatment which begets confidence but not gratitude. He again described his illness as rheumatic fever,

and continued : This is the first day I took to bed altogether: it would have been better to do so before. The pains are only slight… I am sleepy by day and sleepless by night and do not rightly sleep at all.

Kate replied in some alarm, and two days later, on 05 May, Gerard wrote back to her in reassuring tones. He expressed regret at causing her anxiety in his earlier letters, and continued :

The doctor thoroughly examined me yesterday. I have some fever; what has not declared itself. I am to have perfect rest and to take only liquid food. My pains and sleeplessness were due to suspended digestion, which has now been almost cured, but with much distress. There is no hesitation or difficulty about the nurses, with which Dublin is provided, I dare say, better than any other place, but Dr. Redmond this morning said that he must wait further to see the need; for today there is no real difference; only that I feel better.

He referred to some family matters, and then, perhaps in an attempt to finish on a lighter, more cheerful note, he wrote:

It is an ill wind that blows nobody good. My sickness falling at the most pressing time of the University work, there will be the devil to pay. Only there is no harm in saying, that gives me no trouble but an unlooked for relief. At many such a time I have been in a sort of extremity of mind, now I am the placidest soul in the world. And you will see, when I come round, I shall be the better for this. The letter ends I am writing uncomfortably and this is enough for a sick man. I am your loving son. Best love to all. Gerard.

This letter was the last he wrote in his own hand; it would appear that his condition rapidly deteriorated thereafter, for three days later his colleague Father Thomas Wheeler was writing, at his dictation, to Kate. The tone of this letter was positive. My fever is a sort of typhoid; it is not severe, and my mind has never for a moment wandered.

Certainly his mind was not then wandering, as this letter contained a passage explaining in some detail a literary reference he had made in an earlier letter. Hopkins was now under the care of nurses from the nearby St. Vincent's Hospital

. To make caring for him easier, and because of the infectious nature of his illness, he had been moved from his room upstairs at no. 86 St. Stephen's Green to a larger, lighter room on the ground floor of no. 85. His condition was still not causing alarm.

On 14 May, Fr. Wheeler

wrote encouragingly to Kate :

You will be glad to hear that he is still keeping up his strength admirably…I think he is now well round the corner and on the high road to mending…The Drs. are quite pleased with him and the nurses cannot look at the possibility of his being anything but quite well in a short time now… Many prayers have been offered to heaven for him and I feel that they have been heard.

Further evidence of an expectation of his recovery can be adduced from a note in the community accounts book, showing that his boots were sent to be repaired around this time, so as to be ready for his return to work. I digress briefly here to comment on a controversy which arose some years ago in relation to the room in which Hopkins died.

In 1933, the noted Hopkins scholar Humphry House

Norman White

, armed with House's papers, had set out to locate these rooms within the building. He enlisted the assistance of George Williams

, then chief porter at no. 86, who had an intimate knowledge of the building. From House's description, they identified room 18 in no. 86 as that in which Hopkins had lived; this room has since been appropriately furnished, and opened as a memorial to Hopkins.

They then sought to identify the room in which Hopkins died, again using House's description as a guide. They found that the only room which precisely fitted this description was one which had, in the intervening years, been fitted out as toilets—and so remains. This discovery caused some controversy; some felt that this was an ignoble and inappropriate use of the room, while others saw an irony in its present function, given that Hopkins' illness was probably caused, and was certainly exacerbated, by the poor state of sanitation in the house at the time. I offer no opinion on either side of that argument, but make two further brief points. Firstly, I can attach no credence to a subsequent suggestion casting doubt on the identification of the room; this seems to be purely speculative—perhaps born of embarrassment — while the identification was carried out following careful study of House's detailed and precise notes. Secondly, I feel it only fair that no blame should be attached to any of the occupiers of Newman House between 1889 and 1984, in respect of the conversion of the room, which was carried out long before it was identified as that in which Hopkins had died. In any event, it might have been thought more appropriate to mark the room in which Hopkins lived and worked, rather than the one in which he died - which was never in any sense "his" room.

Hopkins' illness had now been diagnosed as typhoid or enteric fever

. This is an infectious disease contracted by eating food or drinking water contaminated by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi

. In areas of poor sanitation it is commonly spread by the contamination of drinking water with sewage.

Sanitary conditions in late 19th century Dublin were poor, and typhoid fever was prevalent - a fact which caused the Dublin Sanitary Association, in 1894, to commission a report on the matter. This report found that the death rate from typhoid fever was higher in Dublin than in any other city in the United Kingdom except Belfast. As part of this investigation, all incidence of the fever in the city for the period 1882 to 1893 was mapped. While the greatest concentration of cases was in the densely inhabited poorer areas in the centre of the city, the report showed a widespread incidence of the disease, including two cases in St. Stephen's Green and several others in nearby streets. Awareness of the public health problems caused by inadequate drainage and sewerage systems led to a decision to construct a major network of main sewers in Dublin. This work was carried out between 1892 and 1906 - too late, alas, for Hopkins.

There are, however, unanswered questions about this diagnosis. One might reasonably wonder why no other member of his community, nor anyone else in the immediate vicinity, caught this highly infectious disease. There is a plausible explanation. It is a documented fact that the drainage system at the University was in a very unsatisfactory condition; after his death, the drains proved, on inspection, to be filthy and overloaded. It is also an undoubted fact, as noted earlier, that Hopkins suffered from generally poor health, and would have had a low level of resistance to infection. possibility; perhaps Hopkins' illness was not typhoid fever. There is some persuasive evidence for this notion. Writing in The Lancet in 1997, Dr. Kenneth Flegel of The Royal Victoria Hospital

, Montreal examined the known details of Hopkins' final illness, and considered them in conjunction with the fact that Hopkins had suffered intermittently throughout his life from diarrhoea, fatigue and eye pain. He came to the conclusion that these conditions, allied to the absence of such typical symptoms of typhoid as headache and fever, indicated that Hopkins' illness was not typhoid fever, but Crohn's disease.

This article led to a response from a group of doctors at St. Thomas' Hospital, London, who put forward a case for coeliac disease. The one point on which they all agreed was that they would never be sure where the truth lay - and neither are we.

We do know that his condition was deteriorating.

Peritonitis was diagnosed on about 04 June, and his parents were summoned from England by telegram. He was initially reluctant to have them come, not wishing them to see him so ill, but, after they had visited, he expressed his happiness at having them there. He gradually declined, and received absolution and the Blessing of the Sick on the morning of Saturday 08 June. He died at 1.30 in the afternoon.

In the Roman Catholic faith, rituals surrounding death are important. The death of a member of a religious community is a significant event in the life of that community; it is their opportunity to show their respect for their colleague, and to send him on his final journey with due solemnity. The funeral arrangements for Fr. Hopkins were put in place, and news of his death was sent to his family in England. They were shocked by the news, not having realised how ill he was. His brother Everard

expressed his grief "that I could not see him once more"

. He was persuaded by his brother Arthur not to attend the funeral. "Perhaps", he said, "it is best for us to remember his sweet and beautiful face as we always knew it - not worn with sickness".

Hopkins' death was reported in The Catholic Times, The Freeman's Journal and The rish Times newspapers. The death notice in the Irish Times of Monday 10 June read as follows:

HOPKINS - June 8, at University College, the Rev. Gerard Hopkins, SJ, Fellow of the Royal University. High Mass and Office at St. Francis Xavier's, Upper Gardiner street, on tomorrow (Tuesday) at 11 o'clock, funeral to Glasnevin immediately afterwards.

On reading this notice, I was struck by how sparse and matter-of-fact it was; unlike modern death notices, it made no mention of his family or religious confreres. His funeral was reported in the same newspaper on Wednesday 12 June, as follows:

The late Rev. Gerald [sic] Hopkins, S.J., F.R.U.I.

Yesterday the remains of this distinguished Jesuit were removed from the Church of the Order, Upper Gardiner street, for interment in Glasnevin Cemetery. Previous to the interment High Mass and Office for the Dead were celebrated in the presence of a large number of clergymen and students of the Catholic University. The celebrant was the Rev. Alfred Murphy, S.J.; deacon, Rev. John Verdon, S.J.; sub-deacon, Rev. Thomas Kelly, S.J. and master of the ceremonies, the Rev. Edward Kelly. The funeral was largely attended. The late Rev. Gerald [sic] Hopkins, S.J., F.R.U.I.

Again, this seems to me to be a mere factual report rather than an obituary notice or tribute. I would suggest that the reason for this is that Hopkins was unknown as a poet at this time; his status derived from his position as a Fellow of the Royal University, and a member of a religious order.

Interestingly, The Nation, a newspaper with whose nationalist stance Hopkins would have had no sympathy, reported his death much more eloquently and elaborately, in its edition of Saturday 15 June. This tribute read, in part, as follows:

Rev. Gerard Hopkins. S.J., whose sad death occurred on Saturday… was a distinguished graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, and a profound classical scholar… on the transfer of University College to its present management he found congenial work within it. As a professor, he aimed at culture as well as the spread of the knowledge of the facts of philology. His tastes were not confined to literature. He was a discriminating art critic, and his aesthetic faculties were highly cultivated. One would have said, before his fatal illness came upon him, that he was just ripe in mind with all his work before him, for he was only forty-four years if [sic] age. He will be missed even from the ranks of the learned Order of which he was a member.

It is interesting to note that Hopkins should receive such a tribute from an avowedly nationalist newspaper. He was markedly anti-nationalist, and was, in particular, antipathetic to Charles Stewart Parnell, the leading Nationalist of his time, who was almost an exact contemporary of his; Parnell was born in 1845, and died - like Hopkins, before his time - in 1891.

Rev. Gerard Hopkins. S.J., whose sad death occurred on Saturday… was a distinguished graduate of Balliol College, Oxford, and a profound classical scholar… on the transfer of University College to its present management he found congenial work within it. As a professor, he aimed at culture as well as the spread of the knowledge of the facts of philology. His tastes were not confined to literature. He was a discriminating art critic, and his aesthetic faculties were highly cultivated. One would have said, before his fatal illness came upon him, that he was just ripe in mind with all his work before him, for he was only forty-four years if [sic] age. He will be missed even from the ranks of the learned Order of which he was a member.

I sought to discover any reference to Hopkins's death in the contemporary Kildare newspapers. I could not locate The Leinster Leader for 1889; I believe that no issues for that year survive. I did find The Kildare Advertiser for that year, but could find no reference to Hopkins' death in the relevant issues.

After a death, life goes on; so it was with Hopkins. His position at University College was filled by another Englishman.

Some years after his death, he was remembered by those at the College 'as a Jesuit who wrote some verse'

.

From the time of his death, his friend and mentor Robert Bridges had in mind the publication of Hopkins' poems. He found the project more difficult than he had imagined, for a number of reasons. He had personal difficulty in writing a memoir of Hopkins, for inclusion with the poems, feeling that he was too close to the subject to write of him objectively. In the decade or so after Hopkins' death, he submitted a number of Hopkins' poems for inclusion in various anthologies, and found himself somewhat discouraged by the disappointing reaction these received. More positive reactions, particularly following the inclusion of a number of poems in the 1916 anthology The Spirit of Man, encouraged him to proceed, and finally, in December of 1918, almost thirty years after Hopkins' death, he presented to Kate Hopkins

the first edition of her son's Poems.

This began a revival of interest in the poetry and personality of Hopkins. Because of that interest, Hopkins still lives. Though his mortal remains have lain in Glasnevin for over a century, he lives in the minds of those who continue to read, study and discuss his work - not least, here, in our midst, during the Hopkins Festival.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2001

- Search the Gerard Manley Hopkins Archive

- Albert Sweitzer and Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Thomas Hardy and poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins

- Christina Rossetti

- Albert Schweitzer and Hopkins

- Hopkins' Use of Imagery in his Porems

- Classical Chinese Poetry and in Hopkins' Poetry

- Inscape, Instress in Hopkins' Poetry

- Parmenides

- Thomas Hardy and Hopkins Poety

- What brought Whitman and Hopkins Close

- Overview Lectures 2001

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2022

- Landscape in Hopkins and Egan Poetry

- Walt Whitman and Hopkins Poetry

- Emily Dickenson and Hopkins Poetry

- Dualism in Hopkins