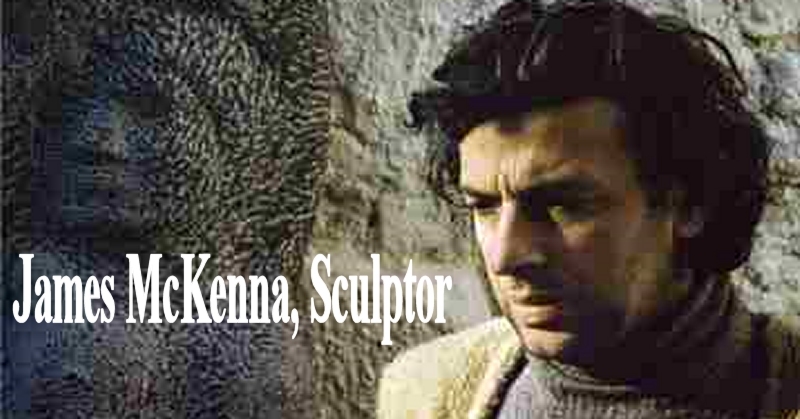

Farewell to Sculptor James McKenna from The Hopkins Festival Committee

JAMES McKENNA (1933—2000)

Oíche dhom go doiligh, dubhach,

Cois farraige na dtonn dtréan,

Ag léir-smaoineadh is ag lúath

Ar choraibh cruadha an tsaol ...

Ba cheart go dtosnófar le cúpla línte filíocht Gaeilge mar bhí an—ghean ag Séamas ar an teanga agus ar an tír. To-day, we think about cora cruadha an tsaoil as we lay to rest a great artist, a sculptor and a great man. A man whose integrity was unique and for which he paid the price of a difficult life, too close to poverty, too far from the favour of that establishment which constantly renews itself. In his Catalogue (1985), James speaks of various works of sculpture 'commissioned by himself'.

It is not the least of the sad ironies that this situation was just beginning to change when he was about to leave us all.

James was a great sculptor, one on speaking terms with the gods of wood and stone. His work at its best has a poetry which you will not exhaust and a kind of terrifying directness that invites comparison with Classical Greek art. He was studying Greek when he died, and I would like to quote a few lines here in the Greek of Callimachus

, the poet's own epitaph,

Here, Desmond read the Original Greek Text followed by the translation

Here lies the son of Battus.

He knew well the art of poesy

And how in season to combine

Friendly laughter with his wine.

Mc Kenna's vision seemed to belong in another age: it was truly epic, as astonishing as his last great horse and rider, 16 feet high and 20 feet long, which he named Oisín Caught in the Time Warp

— this, at a time when the rest of us were struggling within sonnet boundaries.

It would be tempting to pursue the comparison and to suggest that he was a kind of Oisín: heroic, honourable, legendary — except that James did not have much experience of the enchanted Tír na nÓg. A sculptor who never abandoned the figurative and in whose work that great Irish tradition lives on — though he was as daringly modern and experimental within it as anyone could wish. This was at a time of street furniture; at a time when the brief for one tender for a public monument stipulated that it would 'make an impact on a motorist travelling at 70 miles per hour —but not distract him'.

James was an artist who loved Ireland and whose belief in a 32 county Republic, was passionate and unwavering, someone whose own work was suffused in a sense of Irish history and legend (a window into our soul) and never without that compassion without which there can be no great art: witness his tender and beautiful Famine sculpture and drawings. I have seen him become so incensed by the suffering of the Irish in the 17th Century that it seemed not only contemporary but urgent; something to be passionate about.

To the end, he was studying Irish and writing a huge History of Ireland from the earliest times. There was a Bible in medieval Irish (17th Century) by his bed when he died.