Gerard Manley Hopkins: a legacy to the twentieth century

(Delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival and First published by The Irish Jesuits in Studies, an Irish Quarterly Review, 2 (1995)

Elaine Murphy,Organiser,The Hopkins Literary, Festival,

Newbridge, Co. Kildare.

W.H. Gardner describes the permanent worth of Hopkins as a writer:

He is one of the most powerful and profound of our religious poets and is also one of the most satisfying of the so called `nature poets' in English. He is a master of original style and a strikingly successful innovator in poetic language and rhythm. He possessed a unique artistic personality and intense practical concern with those interestswhich inform and shape his poetry, namely his religion, personal reading of nature, his love of people and his critical approach to art and to poetic techniques in particular . . . he succeeded in breaking up, by a kind of creative violence, an outworn convention. He led poetry forward by taking it back-to its primal linguistic origins. He showed how poetry could gain in resourcefulness and power by incorporating in its own artistic processes those natural principles of growth and adaptation which govern our everyday speech ...

He achieved one important kind of perfection which both invites and defies imitation. Hopkins's manner is so essentially a part of the man himself and is so sharply distinctive that anything resembling it seems at once to wear the look of pastiche. No one can really know him without acquiring a higher standard of poetic beauty, a sharper vision of the world, and a deeper sense of the underlying spiritual reality.

The first indication of Hopkins's poetic strength came in Easter 1860 when, at the age of fifteen, he won the Highgate School Poetry Prize for a poem entitled The Escorial

. Two years later, in 1862, he won the Governor's Gold Medal for Latin Verse.

In the spring of 1863, Hopkins went to Balliol College, Oxford

to study Classics - Greek and Roman History and Culture —then at their peak under the mastership of Benjamin Jowett

. He was about to embark on a period which would be the happiest of his young life. His new environment provided him with his first experience of independence and afforded him the necessary stimulus through which he could evaluate and examine his knowledge, beliefs and aspirations.

Hopkins Converts to Roman Catholicism

Hopkins was born into a devout Evangelical

family and raised in the Established Church. Victorian England

was religious. The Victorian era was a tumultuous time for the Church of England. From outside its ranks the Established Church faced open debate about its legitimacy. Within its ranks Bishops fought. The Tractarians, led by Edward Pusey

(and including his protégé, Henry Liddon)

, were fighting to preserve Oxford for the Church of England and one of their goals was to influence students like Hopkins. In 1864 they came under a series of severe tests which were to weaken their cause.

In addition, in February 1864, Charles Kingsley

clashed with John Henry Newman

(a former Tractarian during the first phase of the Oxford movement who in 1833 had converted to the Catholic Church). Newman's Apologia began to be published and brought Newman back to the esteem of the Catholic population as well as to the sympathy of High and Low Church Anglicans. Given his relationships at Oxford, the deep interest in Church matters visible in his letters, it is impossible to think that Hopkins was not keenly aware of the issues involved .

On 17th July 1866, Hopkins `saw clearly the impossibility of staying in the Church of England'. On 28th August 1866, he wrote to Newman: `I am anxious to become a Catholic ...'

When the news of his position became clear to his family, his father urged him to suspend his judgment until his Oxford studies were completed. In a letter to Manley Hopkins (his father), Gerard gave a full account of his position, explaining the futility of any delay in being received in to the Catholic Church: `I cannot fight against God Who calls me to His Church ...

Hopkins was received into the Catholic Church by Newman on the 21st October 1866. The following year, he graduated with a first class degree from Balliol and left the University, first to teach at Newman's Oratory, Birmingham and then to join the Jesuit Novitiate, Roehampton on September 7th 1868. He had considered carefully all that Oxford set before him. Yet despite his family's concern, Liddon's entreaties and Pusey's rejection, he had done `otherwise' and manifested significant form.

Many years later he described the experience poetically in his first major poem The Wreck of the Deutschland. He writes to Robert Bridges:

What refers to myself in the poem is all strictly and literally true and did all occur; nothing is added for poetical padding'.

Stanza three of the poem describes a conversion akin to that of a soldier in the heat of battle:

The frown of his face

Before me, the hurtle of hell

Behind, where, where was a, where was a place?

I whirled out wings that spell

And fled with a fling of the heart to the heart of the Host.

An interesting insight emerges on the subject of Hopkins' conversion, from the contents of his letter to Richard Watson Dixon

, of June 4th 1878. Years earlier, Dixon had taken a mastership at Highgate School for some months while Hopkins was a student there. Hopkins writes:

When you went away you gave, as I recollect, a copy of your book Christ's Company to one of the Masters.... I was curious to read it, which, when I went to Oxford, I did. At first I was surprised at it, then pleased, at last I became so fond of it that I made it, so far as that could be, part of my own mind.

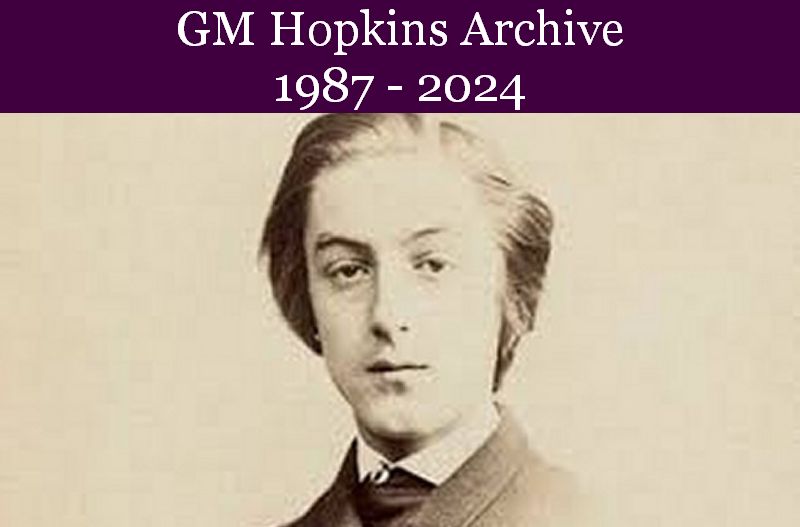

Gerard Manley Hopkins S.J.

Company of Jesus or — I am you see, in Christ's company

. Companions of Jesus

was the original term used for followers of Ignatius of Loyola, who in England were known as the Society of Jesus.

It seems that Hopkins's movement towards conversion, his struggle to express the spiritual and poetic reality of his existence, began as early as seventeen years - if not before. The disciplined life of the priesthood witinh the Jesuit order was the avenue he chose to witness to the divinity of Christ; his poetic gift became the means of its expression.

The effects of conversion are evident in his poetry if we contrast the earlier Escorial, with its precocious display of facts and catalogues works of art, to the mature work. In later years, despite intense suffering, his poems became an eloquent articulation of integrated experience and wholeness. Newman's opinion that formal discipline would bring out the best in him was to prove true, at least in poetic terms, when years later Hopkins' poetic might was to crash over the Canons of English Poetry with the same mighty energies of nature that ran the Deutschland aground.

The first lines of this poem declares the most profound truth of all for Hopkins and heralds a new era for poetry in its finest form:

Wreck of the Deutschland

Thou mastering me

God! giver of breath and bread;

World's strand, sway of the sea;

Lord of living and dead -

Thou has bound bones and veins in me, fastened me flesh,

And after it almost unmade, what with dread,

Thy doing: and dost thou touch me afresh?

Over again I feel thy finger and find thee.

...

Inscape and Instress

Hopkins' youthful interest in Architecture and Art

; his earlier training in sketching and the influence of Ruskin had taught him a way of observing and seeing. Central to his poetry was Inscape, a word which he himself coined to refer to the significant elements which unified and gave its subject its character and form. He made detailed notes in his journal of the essential characteristics of a subject on which he fastened his attention. In addition to determining his subject's Inscape

, he aimed at grasping the essence or stress of its being, its energy, for which he coined the word Instress

.

In 1872, whilst studying for the priesthood, Hopkins began to read the works of the Franciscan, Duns Scotus, and became absorbed with his Principle of Individuation which seemed to speak profoundly to his spirit; e.g. Scotus highlights the difference between the concept `a man' and `Socrates' as due to the specific nature of the individual which sets him apart from any other. To this final individualizing form, Scotus gave the name >Thisness or `Haecceitas.

The fact that Duns Scotus

deeply influenced Hopkins is evident from the last verse of this poem:

Duns Scotus' Oxford

Yet ah! this air I gather and I release

He lived on; these weeds and waters, these walls are what

He haunted who of all men most sways my spirits to peace;

Of realty the rarest-veined unraveller; a not

Rivalled insight, be rival Italy or Greece;

Who fired France for Mary without spot

Theologically Duns Scotus

was the first to clarify and set out the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. Interestingly, The Wreck of the Deutschland, inspired by a shipwreck, was dedicated to the happy memory of five Franciscan nuns, exiles by the Falck Laws

, drowned between midnight and the morning of December 7th 1875 - the vigil of the feast day of the Immaculate Conception.

But Hopkins' interest in Scotus was to cause him grave problems. By the middle of the nineteenth century, St Thomas Aquinas

had become the official theologian of the Roman Catholic Church. His theology was much in vogue at the first Vatican Council (1869-70)

.

Pope

Leo XIII named him the official guide to Catholic thinking in 1879. The Orthodoxy of Thomas Aquinas and the Jesuit Suarez, who mirrored his doctrine, was too powerful to be overcome by the inborn simplicity (or subtlety, if you like) of Scotus and his Franciscan view of nature and knowledge of God through creation to which Hopkins was so attracted. Hopkins failed to pass his Theology exam. According to Fr Joseph Rickaby

he was too Scotist for his examiners. Once again the poet suffered for doing `otherwise' and manifesting significant form.

By this time also, Hopkins had endured rejection for publication of The Wreck of the Deutschland. Fr Coleridge

, Editor of The Month, declined to admit it, after much hesitation, describing it as `unreadable'. Those of us who today, appreciate the depth of poetic truth and beauty in The Wreck of the Deutschland, with its remarkable innovations of technique, can imagine the profound desolation and sense of injustice and neglect the poet must have experienced when his work was rejected. Hopkins' `otherwise' was not the product of a reactionary or rebellious nature. It was the manifestation of `a unique and artistic personality' (Gardner) of which there is ample evidence in his poetry, letters, notebooks and journals.

The Sound of Rhythm's Self

Hopkins was a contemplative, a listener, and his ear was finely tuned. He was sensitive to the rhythm of speech and to the occurrence of sprung rhythms as they occurred in nursery rhymes, jingles, chants, refrains etc. He outlined his poetic theory in a letter to Robert Bridges:

I do not of course claim to have invented sprung rhythms, but only sprung rhythm ... Why do I employ sprung rhythm at all? Because it is the nearest to the rhythm of prose, that is the native and natural rhythm of speech, the least forced, the most rhetorical and emphatic of all possible rhythms, combining as it seems to me, opposite and, one would have thought, incompatible excellences markedness of rhythm — that is rhythm's self - and naturalness of expression for why, if I is forcible in prose to say `lashed rod', am I obliged to weaken this in verse, which ought to be qer, not weaker, into `lashed birth—rod' or something? My verse is less to be read than heard, as I have told you before; it is oratorical, that is the rhythm is so ...

Hopkins was engaged at all times with purging language to regain its freshness and vitality. Extracts from a letter to his brother Everard Hopkins attest the significant form of Hopkins' poetic art: 'I am sweetly soothed by your saying that you cd. make anyone understand my poem by reciting it well. This is what I always hoped, thought and said, it is my precise aim. As poetry is emphatically speech, speech purged of dross like gold in a furnace, so it must have emphatically the essential elements of speech. Now emphasis itself, stress is one of these:

Sprung rhythm makes verse stressy; it purges it to an emphasis as much brighter, livelier, more lustrous than the regular but commonplace emphasis of common rhythm as poetry in general is brighter than common speech ... The natural performance and delivery belonging properly to lyric poetry which is speech, has not been enough cultivated, and shd be. When performers were trained to do it (it needs the rarest gifts) and the audience to appreciate it, it wd be, I am persuaded a lovely art. ... Neither of course do I mean my verse to be recited only. True poetry must be studied. As Shakespeare and all great dramatists have their maximum effect on the stage but bear to be or must be studied at home before or after or both, so I shd wish it to be with my lyric poetry...

In drama the fine spoken utterance has been cultivated and a tradition established, but everything is most highly wrought and furthest developed where it is cultivated by itself, fine utterance then will not be best developed in the drama, where gesture and action generally are to play a great part too; it must be developed in recited lyric. Now hitherto this has not been done.

In a letter to Robert Bridges , Hopkins writes:

To do `The Eurydice' justice you must not slovenly read it with the eyes but with your ears as if the paper were declaiming it at you. For instance the line `she had come from a cruise training seamen' read without stress is mere Lloyds Shipping Intelligence; properly read it is quite a different story. Stress is the life of it.

Perhaps the most striking quality to Hopkins' poetry is his mastery of sound technique. To the calligrapher, letters make patterns, make words but Hopkins effectively used patterning in sound technique to energise his work and to enrich, complicate and heighten his language. He studied the sound value of words carefully and the onomatapoetic theory of the origin of language. Using this technique, Hopkins expressed the deeper realms of the spirit of man and thus attracted his reader or listener. Listen to the first line from the poem Spelt from Sibyl's Leaves

:

Earnest, earthless, equal attuneable, vaulty, voluminous ... stupendous

Evening strains to be time's vast womb-of-all, home-of-all, hearse-of all night

This may have appeared obscure to the Victorian, but to the twentieth century reader, brave enough to master the breath, it is fascinating word-play, full of energy. Those of us who have heard his poetry well read will know the truth of the foregoing statements. One becomes aware of a movement in Hopkins' poetry, which when properly heard, uplifts and leaves one strangely energized and in a different state to that which went before.

Inspiration and Trials

We know that much of Hopkins' poetry came from a lighted cave of inspiration as did the art of Michelangelo, who used his gifts as a painter and sculptor to glorify God. Hopkins was a sensitive and serious artist; sensitive to inspiration, serious about technique. In his last poem To R.B. (Robert Bridges

), he writes with delicate precision and in a compact manner on the nature of Inspiration, that elusive and treasured quality most necessary in the making of a poem. He describes the process thus:

The fine delight that fathers thought-the

Spur, live and lancing like the blowpipe flame,

Breathes once and, quenched faster than it came,

Leaves yet the mind a mother of immortal song.

The last lines from this last poem, To R.B. are poignant:

Oh then, if in my lagging lines you miss,

The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation,

My winter world, that scarcely breathes that bliss

Now, yields you, with some sighs, our explanation.

Hopkins was dying. He was bequeathing his legacy, handing his pen back to his Creator. He had integrated all that he was: his humanity, wisdom, learning and artistic ability with a heavenly light and communicated it poetically with grace and inspiration. Finally, in an act of complete trust and abandon, he sent the last of his masterpieces to Robert Bridges, who became his literary executor. Hopkins had swum against the tide - like the salmon making his way upstream to purer waters to breed.

It seems that Richard Watson-Dixon

, Hopkins' former master at Highgate and with whom Hopkins had corresponded regularly, was the only person who urged Hopkins to publish his work stating: As a means of serving... you cannot have a more powerful instrument than in your verse.

Hopkins's response to Dixon was characteristic:

Now if you value what I write, if I do myself much more does our Lord. And if he chooses to avail himself of what I leave at his disposal he can do so with a felicity and with a success which I could never command.

It took a careful Bridges some time after Hopkins' death to finally publish an edition of Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. The 1914-18 War had changed the relevant role of poetry to that which somehow had to articulate the trauma of that era. Perhaps now it was the time for those prophetic `dark sonnets', which speak of the broken spirit of man and his search for a deeper meaning to his life. As the First World War came to an end, in an atmosphere of the dawn of a new era, Hopkins' newly published work met with excitement and attention in poetic circles.

Victory

The battle was won, and the terrible darkness surrounding the poet's spirit had been overcome. Hopkins began to enjoy a growing readership amongst his fellow Jesuits and writers and poets such as Auden and Robert Graves.

His influence on poetry has been continuous in this twentieth century and has not only been confined to writers. It has inspired artists such as Nathan Olivera

to paint a collection entitled The Windhover

; Bruce Oldfield

, the British fashion designer who describes Hopkins as a source of inspiration, someone he would love to have to dinner! Film actress Elizabeth Taylor, in an interview with American Vogue, when asked for her favourite poem, names Gerard Manley Hopkins' The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo

How to keep — is there any any, is there none such, nowhere

known some, bow or brooch or braid or brace, lace, latch or catch or key to keep

Back beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty, beauty, .... from vanishing away?

... and answers with a Golden Echo:

Give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, Beauty's self and Beauty's giver.

Gerard Manley Hopkins' legacy to the twentieth century is not just a literary one. Contained by the purged language and innovative technique of this master poet is the fruit of a contemplative beholder of that `Ancient Beauty', who weighed everything against his love of God and desired only to follow His will as Christ did.

Notes

Phillips, Catherine

(ed), Gerard Manley Hopkins, Selected Letters, Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 282.- Further Studies in Hopkins, eds.

Michael E. Allsopp and David Anthony Downes

, New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc., 1994. - Phillips, op. cit. p. 37.

- Phillips. op. cit. p. 48.

- Phillips, op. cit. p. 92.

- Gardner, op. cit. p. 12.

- Gardner, op. cit. p. 40.

- Phillips, op. cit. pp. 90 — 91.

- >Phillips, op. cit. pp. 216 — 221.

- Phillips, op. cit. p. 97.

- Gardner, op. cit. p. 59.

- Gardner, op. cit. p. 68.

Roberts, Gerald,

Gerard Manley Hopkins, A Literary Life, 1994, p.112.- Phillips, op. cit. p. 163.

- Gardner, op. cit. pp. 52 — 54.

- Gerard Manley Hopkins applies for a teaching position in the Royal University Dublin - autograph copy of letter

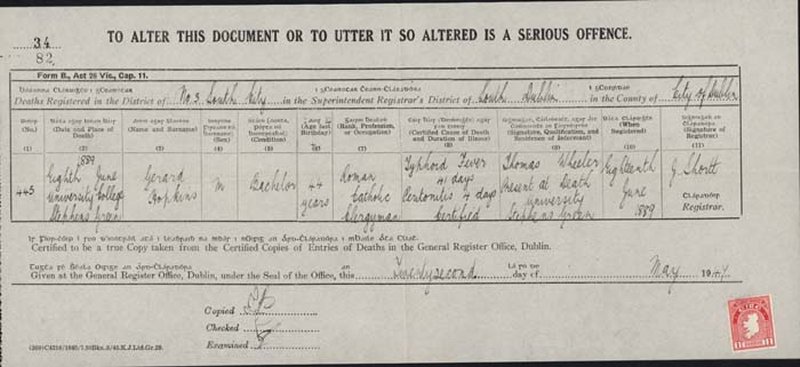

- Hopkins Dies in Dublin and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetry. Patrick Lonergan gives an account of Hopkins's death and funeral

- Gerard Manley Hopkins in Dublin (2012): Michael McGinley

- Hiberno English and Gerard Manley Hopkins's Poetry (2012) : Desmond Egan

Lectures delivered at the Hopkins Literary Festival since 1987

© 2023 A Not for Profit Limited Company reg. no. 268039