How did Jesuit Poet Gerard Manley Hopkins Pray?

This Lecture was delivered at Hopkins Literary Festival 2003Joseph J. Feeney, S.J.,

St. Joseph's,

Philadelphia, USA.

Of course, Gerard Hopkins prayed: as a Christian layman, then as a Jesuit, then as a priest. In Oxford he prayed as an Anglican, high-church in liturgy and evangelical in spirituality bringing this style of prayer with him when he became a Roman Catholic

Of course, Gerard Hopkins prayed: he was a committed Christian layman, then a Jesuit, then a priest. As a young man at Oxford he prayed as an Anglican, high-church in liturgy and evangelical in spirituality. He brought this style of prayer with him when he became a Roman Catholic in 1866, and he brought it with him again when he became a Jesuit in 1868. As a novice he learned new Jesuit styles of prayer— notably "meditation" and "contemplation"— and in his personal prayer he gradually merged these three styles: high-church Anglican, evangelical, and Jesuit.

In this context, then, I pose a rarely asked question, "How did Hopkins pray?" My answer will consider how he prayed (1) in public, (2) in poetry, and (3) in private. With limited time, I focus on prayers directly addressed to God, but will note his more indirect prayer as he finds God in the contemplation of nature. And I deal only with his normal patterns of prayer.

1. Praying in Public

As layman, as Jesuit, and as priest, Hopkins prayed with his varying Christian communities. As an Anglican he regularly attended Holy Communion, and joined in various group devotions: as a child, in family prayers and Bible-reading; as a schoolboy, in daily prayers at the Highgate School; as an undergraduate, in mandatory evening chapel on Sundays which, at Balliol College, was more a lecture than a religious service. At Oxford he sometimes went to morning chapel and Evensong, and also attended the Sunday evening lectures of Canon H.P. Liddon. When on holiday he went, e.g., to morning prayer at Exeter Cathedral.

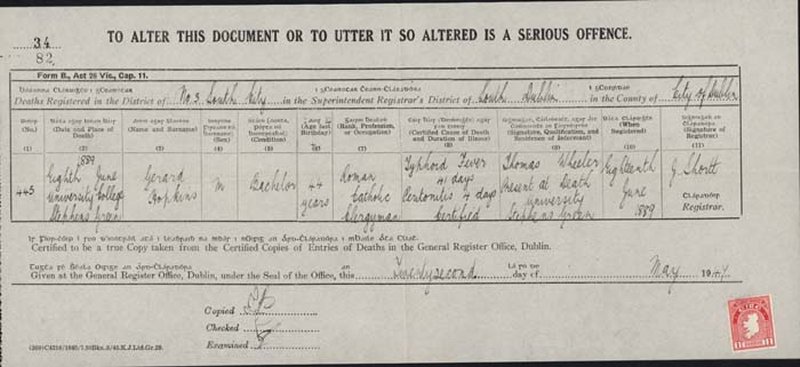

On becoming a Catholic in 1866, Hopkins was dispensed by his College from Anglican services and went to Catholic Mass. In 1867, his last year at Oxford, he prayed with the Benedictines of Hereford Priory at Holy Week and Easter.

The next year, while teaching at J.H. Newman's Oratory School in Birmingham, he again attended Mass and other services as a pious layman.In 1868 Gerard Manley Hopkins became a Jesuit and joined in the prayer of his Jesuit community: Mass in the morning, Litanies in the evening, and the occasional Benediction and triduum. Ordained a priest in 1877, he celebrated Masses, conducted parish devotions, and gave sermons. (His sermons — twenty-six survive— are quite wonderful yet not strictly "prayers," so I don't consider them here.) Yet he wrote one prose prayer that is unique and little known, and deserves note here: it is usually called "A prayer that protestants might use," so-named by Robert Bridges and written in 1883 at the request of Bridges' future mother-in-law. 650-words long and highly Trinitarian, it has three parts: praise, contrition, and love. But its language is traditional and artificial - not at all typical of Hopkins:

Almighty and everlasting God ,... we appear before thee humbly to acknowledge that thou art the one true God, boundless in thy power, wisdom, goodness," or, "Thou, O God, madest us to serve thee," etc. The language comes alive only a few times, but it never flames: "God,... from whose hand we, with all the world besides, every moment take our being"; or, "we...firmly believe those secrets of thy being which man could never know of"; or again, "we wither at thy rebuke, we faint at thy frown, we tremble at thy power." Such are Hopkins' public prayers.

11. Praying in Poetry: Hopkins also prayed in poetry.

In June, 1865, as an Anglican at Oxford highly conscious of sin, he wrote the poem Myself unholy which ends, to Christ I look, on Christ I call. In September, his poem My prayers must meet a brazen heaven concludes, Battling with God is now my prayer.

That autumn his prayers are gentler: one poem invokes music and prays,

I have found the dominant of my range and state —

Love, O my God, to call Thee Love and Love; ...

Love, it grows darker here and Thou art above;

Love, come down to me if Thy name be Love.

That Christmas he prays, directly, Make me pure, Lord: Thou art holy; / Make me meek, Lord: Thou wert lowly. In Lent, 1866, the poem Nondum prays to an absent God — Our prayer seems lost in desert ways, / Our hymn in the vast silence dies - yet ends by begging One word -as when a mother speaks / Soft, when she sees her infant start.Hopkins became a Catholic on October 21, 1866, and his first prayer-poems as a Catholic are translations of the Latin prayer-hymns "Jesu dulcis memoria" and Veni sancte spiritus.

His early Jesuit poems of 1868-75 include similar translations as well as original prayers to God and the Virgin Mary in Latin and English. Hopkins' great ode The Wreck of the Deutschland itself begins with a prayer: Thou mastering me / God! giver of breath and bread.... In Part the First, stanzas 2 and 3 recall a past prayer-experience (I am certain it is his conversion) when God at once terrified him with the prospect of hell and offered his love through the Eucharistic Host. Part the First then ends with a two-stanza prayer to the Trinity that they be adored by all of us. Part the Second similarly ends with a five-stanza prayer to Jesu which begs Christ to burn -to flame - before the shire and to return as Our king back, Oh, upon English souls.Hopkins's grand celebratory sonnets of 1877 - -his annus mirabilis as a poet - overwhelmingly talk about God in praise or petition, but only three speak to God in prayer: Spring asks Christ to preserve the innocent mind and Mayday in girl and boy; In the Valley of the Elwy asks God to complete thy creature dear O where it fails; and The Windhover - if the words thee and chevalier refer to Christ as well as to the kestrel - praises Christ for his magnificent suffering. After Hopkins left St. Beuno's in 1877, many poems are also prayers - mostly prayers of petition, as The Loss of the Eurydice (Save my hero, O Hero savest) or The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe (Be thou then, O thou dear / Mother, my atmosphere, and Fold home, fast fold thy child). Most poignant are his three Dublin prayers - pleas - of petition. No worst cries from futility: Comforter, where, where is your comforting? / Mary, mother of us, where is your relief? [Carrion Comfort] brings the passing, parenthetical gasp (my God!). And Thou are indeed just, first addressing a remote God - Lord, thee, sir, My enemy, my friend, Sir--finally calls out, O thou lord of life, and breaks the heart with its final petition, Send my roots rain.

As I end my comments on Hopkins' prayer—poems, I note that not all of his prayerful poems are formal prayers: many are statements rather than prayers, or are addressed to someone other than God or the saints, but are deeply prayerful: such great meditative poems as God's Grandeur, The Starlight Night, As kingfishers catch fire, Pied Beauty, Hurrahing in Harvest,and "That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection." 111.

Praying in Private

Perhaps most intriguing is the question of how Hopkins prayed when he was alone before God, for here we enter his most private self and perhaps his deepest contact with God. Yet where can we find data?

How can we possibly know how he prayed when he was alone before God? The answer, I suggest, lies in three places: his notes from his 1883 Retreat, his points for meditation of 1884—1885, and his notes from his 1889 retreat (my time limited, I consider only the second, as his more typical prayer). For context, I note the two basic styles of Jesuit prayer: meditation which stresses thinking and reflecting, and contemplation which stresses seeing, hearing, even smelling and touching some Biblical event. Both end with direct addresses to God called colloquies. Some Jesuits, I add, practice an illuminative prayer of more direct union with God. In Dublin, following what seems his lifelong pattern, Hopkins commonly prepared points—a short list or "set" of topics or events—to use in his prayer the next morning.

The surviving twenty-five sets of points follow the pattern of the Exercises, and date from just before his Terrible Sonnets, i.e., from February 22, 1884 to March 25, 1875. His subjects include Christ, the saints, Gospel characters (including devils), the Blessed Sacrament, and Wisdom. An example conveys the general flavor, using the common three-part division of the Exercises: Dec. 24, christmas eve—Mary and Joseph were poor, strangers, travelers, married, that is to say / respectable, honest; for this is a condition in charity to consider to whom you give and family life is the greatest safeguard their trials were hurry, discomfort, cold, inhospitality, dishonour their comfort was christ's birth. thank god for your delivery of today [a gift?]. here think yourself the gloria in excelsis and bring yourself to leave out of sight your own trials rejoicing over christ's birth. wish a happy christmas and all its blessings to all your friends. These sets of points do not in themselves show whether Hopkins prayed by meditating or contemplating.

Sometimes he proposes ideas, as if for meditation: Consider what men now say of Christ, Consider the Blessed Sacrament as put into your hands. At other times he proposes physical material, as if for contemplation: The crown is of thorns. Consider Christ's bodily pain, or, I see the Lord before me etc. But even words like consider or remark point towards a more physical, participative use of his material, suggesting that by 1884 Hopkins' mature prayer, after sixteen years as a Jesuit, tended towards contemplation. In preparing his points for prayer, I add, he also planned - pointed towards - a hoped-for spiritual result in himself: Crown him king over yourself, of your heart, or Here admire our Lord in this struggle, or Therefore I rejoice.In sum, Hopkins' private prayer seems to involve both meditation and contemplation, but contemplation prevails. Both styles evoked emotional responses and direct addresses to God during his prayer and - most important - a longer, concluding prayer, a closing colloquy, seems to have brought a deep love and affection for his God. That, so far as I can determine, is how Hopkins prayed in normal times.

With my time short, I leave for another year and another lecture a consideration of his abnormal prayer, e.g., the day in his 1883 retreat when he was advised not to dwell on past sins, or the lost contact with God recorded in the Terrible Sonnets of 1885-86, or the helpless loathing he felt in his 1889 retreat - a retreat which he made, by the way, just some twenty five or so miles west of here, in Tullabeg.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2003

- Scottish View of Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Explore other areas of The Hopkins Archive

- Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Climb to Transcendence

- Hart Crane and Gerard Manley Hopkins

- How Father Hopkins SJ Prays

- Oscar Wilde and Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Flannery O Connor and Hopkins

- Levelling with God

- Polish writer Norwid and Hopkins influence

- Walker Percy and Gerard Manley Hopkins