Father Gerard Hopkins, S.J. makes his Annual Retreat

Joseph J. Feeney, S.J.,St. Joseph's,

Philadelphia, USA>

Gerard Manley Hopkins makes his annual retreat, usually following the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola to look back over the past year in the sight of God.

What is the Annual Retreat?

Each year, every Jesuit - including Fr. Gerard Hopkins, S.J. — makes his "annual retreat," eight days of prayer and silence, usually following the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Its purpose is to look back over the past year in the sight of God, to thank God for what has gone well, to face problems that may have occurred, and to do planning - perhaps make resolutions - for the following year. The operative question is, "How can I better serve God?" This annual retreat is usually a time of peace and quiet - not anguished at all, but rather, a visit with the Trinity and the saints to see how each individual Jesuit stands in their company and how he can better serve God.

The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola is a handbook for making a retreat, carefully balancing sin, grace, love, and service, always with a sense of the positive, of the world as redeemed in Christ. To explain what Fr. Hopkins did during his annual retreat, then, may I first explain what a "retreat" is? A Jesuit retreat has six parts:

- An opening "Principle and Foundation,

- Weeks 2 — 5 four "Weeks"

- Week 6 a closing "Contemplation to Obtain Love."

The "Weeks," I add, have nothing to do with seven days, but are simply a way to group the content. It is helpful briefly to summarize each of the six parts of a retreat. (1) The "Principle and Foundation" ponders the basics: Humans are created to praise, reverence, and serve God, and thus save their souls; everything else is created to help them toward this goal, therefore they should use the things that help and avoid the things that don't. (2)

The "First Week" meditates on the world's sin, on my sin, on hell, and on Christ who saved us from sin and from hell. Its purpose is to clear out the ugly mess of sin, and have our sins forgiven.

(3) The "Second Week" focuses on Christ calling us to follow him, and contemplates his incarnation, birth, and public life — all done for me. Its purpose is to increase our love of Christ, and help us to choose how best to follow him.

(4) The "Third Week" contemplates Christ's suffering and death —all for me and my sins. Its purpose is to feel his sorrow, to increase our love even more, and to prepare us for the sufferings we'll experience in following him.

(5) The "Fourth Week" contemplates Christ's resurrection, appearances, and ascension. Its purpose is to have us rejoice with him and in our service of him. (6) Finally, "The Contemplation to Obtain Love" is the climax—-the very positive climax — of the retreat. It begins with two comments on love: "Love ought to manifest itself more by deeds than by words," and "Love consists in a mutual communication between two persons."1 It then goes on to contemplate four grounds for loving God: his gifts to me personally, his presence in all his creatures, his work for me through all creatures (God is "one who is laboring"(2), and "how all good things and gifts descend from above."(3) Throughout all this, Ignatius is quite practical: "You, Lord, have given all that to me. I now give it back to you," and my gratitude urges me to "love and serve the Divine Majesty in all things."(4)

Such is an Ignatian retreat, such the content of "The Spiritual Exercises."

During his 21 years of Jesuit life Hopkins made 22 retreats. Twenty were eight-day retreats, and two were "Long Retreats" — retreats of thirty days at the beginning and end of his Jesuit training, i.e., in 1868 as a novice and in 1881 as a tertian. Hopkins likely took notes during all these retreats, and as a tertian began to write a "Commentary" on the Spiritual Exercises.(5) Besides part of this "Commentary," two sets of his retreat notes survive, both from eight-day retreats: in September 1883, at Beaumont Lodge, near Windsor, England, and in January 1889, at Tullabeg, near Tullamore, Co. Offaly, Ireland.

Hopkins on Retreat, September 1883

At the time of his 1883 retreat, Hopkins was 39 years old and teaching at Stonyhurst College. His retreat was a time of peace, with about half the days given to the First Week, though his notes are incomplete. During the First Week, a review of his own past sins brought "an old and terribly afflicting thought and disgust [which] drove me to Fr Kingdon," who well advised him "not further to dwell on the thought." He then had "lights" — insights —when meditating "on the Particular Judgment." In the Second Week, pondering the Baptism of Christ, he felt warm devotion: "Our Lord asked Our Lady's blessing on his work and I thought how good it was to ask her blessing on anything we undertake." He was not troubled by his lack of "hard penances," for" a great part of life to the holiest of men consists in the well performance, the performance, one may say, of ordinary duties." He also prays that "God will lift me above myself to a higher state of grace, in which I may have more union with him, be more zealous to do his will, and freer from sin," and notes that "yesterday night it was 15 years exactly since I came to the Society." Meditating on Christ's Temptation in the Desert, he took on the mood of Christ: "I was with our Lord in the wilderness in spirit."

He also had other "good thoughts I do not put down," and touchingly added,

Also in some med[itation] today I earnestly asked our Lord to watch over my compositions, not to preserve them from being lost or coming to nothing,...[but that God] should have them as his own and employ or not employ them as he should see fit. And this I believe is heard[.]

In the Third Week, his meditation on the Crucifixion made him realize that asking for more grace was "asking also to be lifted on a higher cross. Then I took it that our Lord recommended me to our Lady and her to me." In the Fourth Week, he made the meditation on the Walk to Emmaus "in a desolate frame of mind," but "was able to rejoice in the comfort our Lord gave those two men." He even realized that this comfort "was meant to be of universal comfort to men and therefore to me and that this was all I really needed." As a final note he humbly added, "It was better for me to be accompanying our Lord in his comfort of them than to want him to come my way to comfort me." (6) Peace and gentleness mark this 1883 retreat. He clearly was living with God, and his prayer also stimulated fresh, original theological thought.

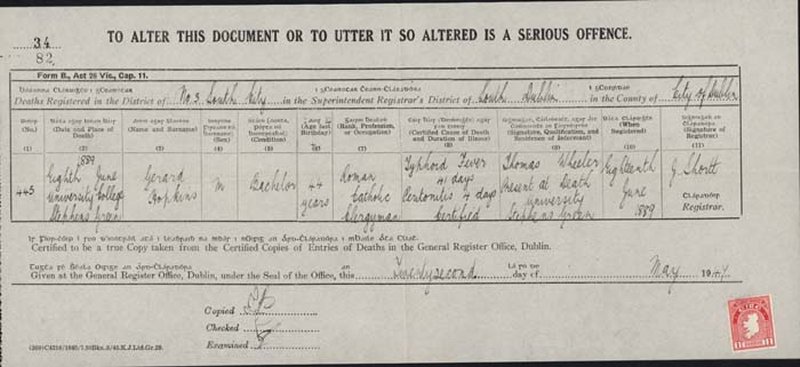

In 1889 in Ireland, the mood of his retreat was quite different. He began his retreat on January 1, coming to the retreat exhausted from teaching at University College and from examining Classics students from all of Ireland. Such work he thought fruitless. He was also irritated by smoky Dublin and, as a patriotic Englishman, by the Irish campaign for Home Rule. He had also endured a spiritual and psychological depression in 1885. Thus, the Principle and Foundation evoked a heartrending cry brought, it seems, by his meditation on the words "serve God":

But how is it with me? I was a Christian from birth

or baptism, later I was converted to the Catholic

faith, and am enlisted 20 years in the Society of

Jesus. I am now 44. I do not waiver in my allegiance,

I never have since my conversion to the Church. The

question is how I advance the side I serve on...

I was continuing this train of thought this

evening when I began to enter on that course of

loathing or hopelessness which I have so often felt

before, which made me fear madness.... What is my

wretched life? Five wasted years almost have passed in

Ireland. I am ashamed of the little I have done, of my

waste of time, although my helplessness and weakness

is such that I could scarcely do otherwise.... All

my undertakings miscarry: I am like a straining

eunuch. I wish then for death: yet if I died now I

should die imperfect, no master of myself, and that is

the worst failure of all. O my God look down on me[.] (7)

It is notable, I add, that he never mentioned his "compositions" here.

In this retreat, the First Week again lasts about four days, but both Day 2 and Day 3 bring "loathing."(8) The Second Week brings meditations on the Incarnation and the Nativity, with distracting thoughts on Pompey, Caesar, and the Roman Empire. It also brings the striking comment that "my life is determined by the Incarnation down to most of the details of the day": an amazing statement about his success in modeling himself after Christ.(9) Day 6, the feast of the Epiphany, brings thoughts <p align="center">really distractions <p align="center"> about the Magi and their background, about astronomy and astrology, and about the time of the Magi's arrival. By this point, Hopkins is doing more thinking than praying. His contemplation of Christ's Baptism again brings distractions, as do his reflections on Nathaniel, Philip, and the Marriage Feast of Cana. Such thinking and writing, often theological, keep to the structure of the Exercises, and may have saved him from renewing the anguish of the retreat's opening day and its "loathing." There the notes end, in the middle of the Third Week.

Such are the retreat notes which still exist from Hopkins' 22 retreats. Add in his commentary on the Exercises and his Dublin "points" for morning prayer, and a conclusion grows clear: Gerard Hopkins, poet and priest, was a devoted Jesuit deeply committed to the spirituality of Ignatius Loyola.

As for the influence of the Exercises on his poetry in content and in structure, that is for another lecture, another time, another year. But as a final comment I might note that his poems "Harry Ploughman" and "Tom's Garland" were both conceived, and partly written, during his 1887 annual retreat in Dromore, Co. Down (now in Northern Ireland). Surely they were a distraction, as he thought about social problems, and rhythm, and how to write codas. But they were part of his annual retreat - a holy, fertile time for Fr. Gerard Hopkins, S.J.

Notes

1. George E. Ganss, S.J., tr. and ed., The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius: A Translation and Commentary (St. Louis: The Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1992), p. 94.

2. Spiritual Exercises , p. 95.

3. Spiritual Exercises , p. 95.

4. Spiritual Exercises , pp. 94-95.

5. The Sermons and Devotional Writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins , ed. Christopher Devlin, S.J. (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), pp. 122-209

6. Sermons , pp. 253-54.

7. Sermons , pp. 261-62.

8. Sermons , pp. 262-63.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2007

Elizabeth Bishop and Hopkins Poetry

Aubrey de Vere and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Patrick Kavanagh and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Communion of Saints in Hopkins Poetry

Place of Church in Hopkins Juvenile Poems