On the Road with Gerard Manley Hopkins

Sister Jeanne Crapo,Dominican University,

River Forest,

Illinois, USA

Gerard Manley Hopkins poems tell of God's ways. In The Wreck, the picture of tempest and terror, with the tall nun standing on the deck and crying "Christ, Christ come quickly!" Hopkins is moved by her courage and her eagerness to meet Christ.

Margaret Johnson

in her essay, "These Things were There," says of Hopkins' poetry, "How can I deal with poetry that sees, even in apparent absence, the perpetual presence of God" (71). How indeed! It is a challenge.

In the "Wreck of the Deutschland" the first poem after the seven year silence, the poet tells of God's ways with him and then turns to the story of the sinking ship itself. In the picture of tempest and terror, he tells of the tall nun standing on the deck and crying "Christ, Christ come quickly!" He is moved by her courage and her eagerness to meet Christ. In the final stanza of the poem he prays to her :

Dame at our door

Drowned, and among our shoals

Remember us in the roads . . .

It is these roads, that age-old metaphor for life, that hold my interest.

The poems that followed "Wreck of the Deutschland" were experimental, exuberant poems, overflowing with love of God, reflecting Hopkins' God-centered life of Mass, prayer, meditation. The Breviary, with the Psalms, was not casual spiritual reading for Hopkins but an integral part of his daily prayer. Surely the Psalms, pointing the reader heavenward, influenced his own songs. We can place Hopkins' poetry with the Psalms, Piers Plowman , Pilgrim's Progress , and Herbert

's The Temple , as showing the reader ways to move heavenward.

Norman White

in his recent book Hopkins in Ireland comments on Hopkins' poetry: "And therefore, it was a primary condition of Hopkins' poems written as a Jesuit before the 1885 Dublin sonnets that they have as motivation and justification the Jesuit proselytizing purpose" (23). If this is so, it is surely one proselytizer to another proselytizer, for no one insists you agree with him more than Norman White. I believe Hopkins wrote with heart overflowing with wonder, gratitude, and love, seeing in the world God's distinct footprints. And the poet draws the reader to see things his way. Also the structure of the Italian sonnet which Hopkins chose lends itself to the Ignatian meditation : presentation of scene, reasoning, explanation, and application. Hopkins expanded the form, adding codas and outrides . All of his life he had an audience of two, Robert Bridges

and Canon Dixon

. Hopkins sent his poems to Bridges to be kept for him-fair copy. This correspondence and friendship are the reasons we have his poems. In one letter, Bridges apparently has taken Hopkins to task for obscurity and oddness. In his reply, Hopkins takes words and rhymes from "The Sea and the Skylark" explaining the meaning of each. When he gets to the word rash-fresh, he stops in the midst of a sentence and says, "it is dreadful to explain these things in cold blood." (Letter XCIII, Nov. 16, 1882) In this paper, I feel I am taking lines and phrases out of Hopkins' beautiful poetry in cold blood to make my point. . The poems of 1877, the year of his ordination, were filled with love for God and the desire to show the glory of God in the beauty of the natural world. We know the lovely poems : " God's Grandeur ," "Pied Beauty," "Spring," and a summation in "Hurrahing in Harvest" :

I walk, I lift up, I lift up heart, eyes,

Down all that glory in the heavens to glean our Saviour; (38)

"The Windhover"

>demonstrates by the mastery of the kestrel Christ's mastery in his ministry, and Hopkins on the eve of his entry into a formal ministry wishes as the heart - in-hiding to emulate Him, to buckle in himself the glorious attributes of Christ. In the final three lines, however, the poet turns to the ordinary tasks of daily living :

No wonder of it: sheer plod makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

After showing the glorious mastery of the bird, the poet turns to the ordinary, the hard labor to make the ground ready for the seed, the hidden person, unknown, compared to the embers which are drab and dull but in the moment of doing flash gold vermillion. Perhaps, hidden, ordinary duties achieved.

In "The Starlight Night

" the poet discovers the piece-bright paling which shuts Christ from view--the

spiritual reality of heaven a purchase, the prize of "Prayer, patience, alms, vows." Companions along road of life are specifically looked at in "A Lantern out of Door"

Men go by me whom either beauty bright

In mould of mind or whatever makes rare

They rain against our much-thick and marsh air

Rich beams, till death or distance buys them quite.

When loved ones no longer walk beside us, when a person is with us, then suddenly not, what to do? Give them to Christ, "their ransom, their rescue, and first, fast, last friend." We know the roads Hopkins traveled because of the wonderful mosaic of letters, sermons, and journals: St. Beuno's, Stonyhurst, Roehampton, Derbyshire, Oxford, Bedford Leigh, Liverpool, Glasgow, Dublin. It is not that the poetry shows us a different man from the prose. It's just that the poems go straight to the mark, to show the way. heavenward.

When stationed in Oxford, Hopkins had care of the barracks and here we glimpse the priestly duty in "The Bugler's First Communion." We know the exact date, July 27, 1879. A young bugler approached Hopkins with the request that he make his First Communion. The duty delights the priest: "Forth Christ from cupboard fetched," and then the priest prays the angel-warder to protect the young man:

Frowning and forefending angel-warder

Squander the hell-rook ranks sally to molest him;

March, kind comrade, abreast him;

Dress his days to a dexterous and starlight order.

Of the Liverpool work, Hopkins writes to Canon Dixon

, "The parish work of Liverpool is very wearying to mind and body and leaves me nothing but odds and ends of time. There is merit in it, but little Muse" (Letter XI Liverpool, May 4, 1880). Hopkins complains of inability to do anything, of jadedness. Yet there is no sign of this in the lovely poem written at the time: "Felix Randal." ' Felix Randal the farrier, O is he dead then? My duty all ended.' This poem shows the priest's compassion and care in the anointing of the sick which brought a heavenlier heart to Felix, but the poet does not leave the reader with the image of the sick and dying man. By beautiful contrast, the poet turns to Felix's early manhood when he was maker of the "bright and battering sandal."

In "The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air we Breathe" written at Stonyhurst,

the reader is drawn to better understand the wonders of the Incarnation and Mary's place in that mystery:

Through her we may see him

Made sweeter, not made dim,

And her hand leaves his light

Sifted to suit our sight,

Bridges and Canon Dixon

tried to get Hopkins to agree to publication of some of his poetry . Hopkins always replied with an emphatic no. In a letter to Canon Dixon, Nov . 11, 1881, he offers an explanation, not of his not publishing, but of his sense of the value of the poetry :

'I am ashamed at the expression of high regard which your last letter and others have contained . . . The question then for me is not whether I am willing . . . to make a sacrifice of hopes of fame . . . , but whether I am not to undergo a severe judgment from God for the lothness I have shown in making it, for the reserves may have in my heart made, for the backward glances I have given with my hand upon the plough, for the waste of time the very compositions you admire may have caused and their preoccupation of the mind which belonged to more sacred or more binding duties, for the disquiet and the thoughts of vain-glory they have given rise to. (Letter XXI).

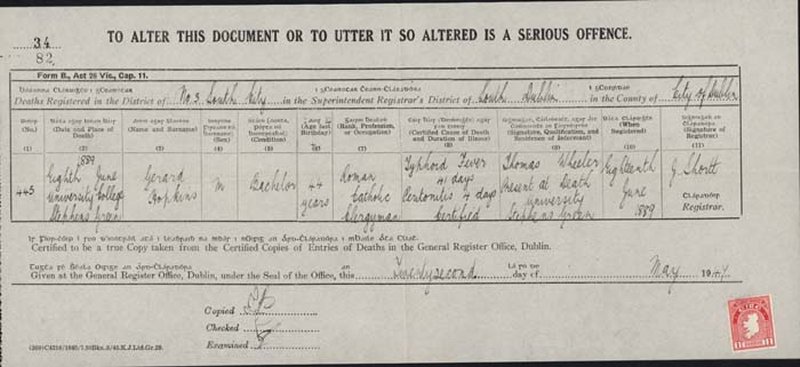

And later to Bridges he says in the same vein: "It always seems to me that poetry is unprofessional, but that is what I have said to myself, not others to me"(Letter CVII) . After a year and a half teaching at Stonyhurst, Hopkins was appointed to Dublin, to the Royal University of Ireland and to the faculty at University College to teach Latin and Greek and to read examinations. There was a row over his appointment – he was an Englishman at a time when all Ireland was wishing for Home Rule

. These times were difficult . Hopkins had for years suffered from depression. Here again it was the case, exacerbated by declining health, the arduous examination grading, his family outside the Church, and the fact that his colleagues and his students sided with the rebels. Paul Mariani

in his book A Commentary on the Complete Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins

, comments: 'Although not yet forty, Hopkins felt that his poetic vein was thinning out. But when removed from Stonyhurst to Dublin and isolated from friends, family, and countrymen, he was coaxed by his muse to write again, there is a radical trans- formation in Hopkins' poetic voice which touches on the darkness of Lear in its confrontation, not with the world without, but with the self within (192) .

These Dublin poems are cries of anguish as well as testaments to faith. Read together they offer a picture of the poet's confrontation with God, his realization of total unworthiness, and the inability to act. Seemingly, God has withdrawn and only the self remains:

And my lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

To dearest him that lives alas! Away

. . .

I am gall, I am heartburn. God's most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste; my taste was me;

With the anguish, however, came the understanding, the reason for the pain.: Why? That my chaff might fly; my grain lie, sheer and clear

As the reader moves with the poet, Pitched past pitch of grief, the poet counsels patience:

Patience, hard thing! The hard thing but to pray.

But bid for, Patience is! Patience who asks

Wants war. Wants wounds; weary his times, his tasks

To do without, take tosses, and obey.

. . .

We hear our hearts grate on themselves; it kills

To bruise them dearer, yet the rebellious wills

Of us we do bid God bend to him even so.

In "My own heart let me more have pity on,"- a kind of reasonableness returns after the storm:

Soul, self; come poor jackself, I do advise

You jaded, let be; call off thoughts awhile

Elsewhere; leave comfort root-room;

And the poet in "The Heraclitean Fire and the Comfort of the Resurrection" affirms the wonder and comfort of the new life of resurrection:

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, patch, matchwood, immortal

diamond,

Is immortal diamond.

We know from all the sources that Hopkins' greatest desire was to be transformed into Christ and to draw souls to Christ . His prayer at the end of the "Wreck of the Deutschland" tells us this :

Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us,

Be a crimson-cresseted east.

So these poems, these non-professional utterances, these compositions which he said took his mind away from "more sacred and binding duties" have been, for the generations who have read and loved them, "A lamp to our feet, and a light to our path."

I would like to close with a poem written by Sister Jeremy Finnegan

, a sister of my congregation . It was published in 1947.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

The stress of death came to the weary mind

Sworn to infinity and nothing less;

Thankful to feel at last the last duress

And leave the rack of living far behind.

Lone, lost, Gerard-forespent you were, not blind

Who learned in stormy darkness to assess

The cost of the irrevocable yes

That locks the life where no conjectures find.

Go praised, therefore and honored by strange tongues

Whose loyalties fall short of your fair choice

To slip the part and win the excelling whole,

You have by purchase now your starry rungs

And we the cadence of an anguished voice :

I am gall. I am heartburn. Were. God rest your soul.

Works Cited

Abbott, Claude C

. ed. The Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges. London: Oxford UP, 1935.

— Correspondence of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Richard N. Dixon. London: Oxford UP, 1935.

Finnegan, Sister Jeremy

. Dialogue with an Angel. New York: Devin-Adair, 1947.

Gardner, W. H. and N.H. MacKenzi

e. The Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Fourth Edition. New York: Oxford UP, 1967.

Johnson, Margaret

. "These Things were There," In Hopkins Variations. Joaquin Kuhn and Joseph Feeney, S.J. eds. Philadelphia: St. Joseph's UP, and New York: Fordham UP, 2002.

Mariani, Paul. Commentary on the Complete Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1970.

White, Norman.

Hopkins in Ireland. Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2002.

Links to Hopkins Literary Festival 2007

Elizabeth Bishop and Hopkins Poetry

Aubrey de Vere and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Patrick Kavanagh and Gerard Manley Hopkins

Communion of Saints in Hopkins Poetry

Place of Church in Hopkins Juvenile Poems